Hildegard of Bingen Was Born Into a _____ Noble Family

Hildegard of Bingen (also known every bit Hildegarde von Bingen, l. 1098-1179 CE) was a Christian mystic, Benedictine abbess, and polymath adept in philosophy, musical composition, herbology, medieval literature, cosmology, medicine, biology, theology, and natural history. She refused to exist defined by the patriarchal hierarchy of the church building and, although she abided by its strictures, pushed the established boundaries for women most past their limits.

Forth with her impressive torso of work and ethereal musical compositions, Hildegard is best known for her spiritual concept of Viriditas – "greenness" - the cosmic life forcefulness infusing the natural world. For Hildegard, the Divine manifested itself and was credible in nature. Nature itself was not the Divine but the natural world gave proof of, existed because of, and glorified God. She is also known for her writings on the concept of Sapientia – Divine Wisdom – specifically immanent Feminine Divine Wisdom which draws close to and nurtures the human soul.

From a young age, she experienced ecstatic visions of calorie-free and audio, which she interpreted equally letters from God. These visions were authenticated by ecclesiastical authorities, who encouraged her to write her experiences down. She would get famous in her own lifetime for her visions, wisdom, writings, and musical compositions, and her counsel was sought by nobility throughout Europe.

Early Life & Teaching

Hildegard came from an upper-class German family, the youngest of ten children. She was often ill as a child, afflicted with headaches which accompanied her visions, from around the historic period of three. Whether her parents consulted physicians about her wellness problems is unknown, just at the age of seven, they sent her to be enrolled as a novice in the convent of Disibodenberg.

Hildegard had feared & resisted her visions but was supported & encouraged to accept them by Volmar.

Hildegard was placed under the care of Abbess Jutta von Sponheim (l. 1091-1136 CE), head of the order, an aristocrat and girl of a count who had chosen the monastic life for herself. Jutta was only half dozen years older than Hildegard in 1105 CE when the latter entered the convent and the two would get close friends. Jutta taught Hildegard to read and write, how to recite the prayers, and introduced her to music by instruction her to play the psaltery (a stringed musical instrument like a zither). Jutta may likewise accept instructed the younger girl in Latin (though this merits has been challenged) and encouraged her to read widely.

During this time, she was as well instructed past a monk named Volmar (d. 1173 CE) who served as prior to the convent and the nuns' confessor (since women were not allowed to hear confession, celebrate Mass, or preside over whatever official assembly other than meetings of other women regarding the day-to-day upkeep of their community). Hildegard had told Jutta about her visions, and Jutta felt it her duty to inform Volmar. Volmar encouraged Hildegard to believe in the actuality of the visions and to write about them. He may have also been the one to teach her Latin and introduce her to various forms of literature. After seven years of tutelage and service, at the age of 14, Hildegard made her profession of organized religion and was accepted into the social club.

St. Hildegard Meeting St. Jutta of Sponheim

Hildegard and Jutta were typical of the nuns at this fourth dimension in that they came from upper-course, aloof families who could afford to pay the Church to have their daughters. Although it was officially forbidden to accept coin from parents, nunneries required a substantial 'dowry' for a girl to be accustomed, claiming information technology would become to her budget. These dowries took the form of deeds to lands, cash, expensive clothing, and similar valuables. Daughters of poor families could not beget the dowry and, if they wanted to participate in convent life, information technology was as maids or cooks. Scholars Frances and Joseph Gies comment on the attraction of the convent for young women in the Middle Ages:

For upper-form women, the convent filled several basic needs. It provided an alternative to marriage by receiving girls whose families were unable to detect them husbands. It provided an outlet for nonconformists, women who did not wish to ally because they felt a religious vocation, because union was repugnant, or because they saw in the convent a mode of life in which they could perform and perhaps distinguish themselves. The nunnery was a refuge of female intellectuals. (64)

Hildegard certainly fit this paradigm of the female person intellectual, distinguishing herself by her vast learning, devotion to God, and service to others. When Jutta died in 1136 CE, Hildegard, and then 38 years old, was unanimously chosen to succeed her.

Visions & Move to Rupertsberg

From the time she was young, Hildegard had feared and resisted her visions simply was supported and encouraged to accept them by Volmar. A few years afterward becoming abbess, she began receiving the visions more vividly than before and with such frequency that she became bed-ridden. She had confessed her visions to the Abbot Kuno, who presided over her social club, and he encouraged her to write about them, but she refused.

The visions themselves then became insistent that she write them down and interpret them for an audience. Hildegard resisted until she fell into delirium in which the visions, constantly recurring, demanded she express them in writing. She relates:

In this affliction I lay thirty days while my torso burned as with fever…And throughout those days I watched a procession of angels innumerable who fought aslope Michael against the dragon and won the victory. And i of them chosen out to me, 'Eagle! Eagle! Why Sleepest thou? Ascend! For information technology is dawn – and eat and potable!' Instantly my body and my senses came back into the world and, seeing this, my daughters [swain nuns] who were weeping effectually me lifted me from the ground and placed me on my bed and thus I began to go my strength back. (Gies, 78)

Encouraged past Volmar and Abbot Kuno and inspired by the visions themselves, Hildegard began to write her best-known work, the Scivias (shortened form of the Latin Scito vias Domini – "Know the Way of the Lord"– , composed c. 1142-1151 CE) which, in accord with her visions' instructions, related what she saw and what she felt they meant. By this time, she was a well-established visionary, renowned for her wisdom, and much sought afterwards for counsel. Pope Eugenius (served 1145-1153 CE) read parts of the Scivias, approved the visions as accurate revelations, and encouraged Hildegard to continue the work. People would visit Disibodenberg to seek her out and, later, would have been gently reminded by Abbot Kuno to leave a donation before they departed.

Ruins of Disibodenberg Monastery

In 1147 CE, Hildegard requested get out to found her ain convent in Rupertsberg, 65 miles (105 km) to the due south-eastward. Her asking sparked a dispute with Abbot Kuno who denied her permission and suggested she accept the position of Prioress at Disibodenberg and place herself under his potency. His reasons for refusal are never recorded but most likely he was reluctant to lose so great an asset equally Hildegard who non only brought in significant revenue only managed to keep the convent running efficiently and conduct correspondence with important figures who might be inclined to donate farther.

Hildegard refused to accept Kuno's decision, repeated her request, and when Kuno denied her a second time, she took the matter to the Archbishop of Mainz who approved it. Kuno still would not release her or the nuns until Hildegard, bed-ridden (perhaps due to her visions), informed him that God himself was punishing her for non following his will in moving the nuns to Rupertsberg. Hildegard was stricken with a paralysis so astringent that no one could move her arms or legs and, after witnessing this, Kuno relented and allowed the nuns to leave. Hildegard established the convent at Rupertsberg c. 1150 CE with 18 nuns and her friend the monk Volmar every bit their confessor.

Works & Beliefs

Hildegard'due south vision is extensive in scope, far transcending the common vision of the medieval Church while still remaining within the bounds of orthodoxy. She claimed the Divine was every bit female in spirit every bit male and that both these elements were essential for wholeness. Her concept of Viriditas elevated the natural earth from the Church's view of a fallen realm of Satan to an expression and extension of the Divine. God was revealed in nature, and the grass, flowers, trees, and animals bore witness to the Divine simply by their existence.

Hildegard'due south Ordo Virtutum is the oldest medieval morality play & the simply medieval musical extant.

Her start major piece of work, the Scivias, relates 26 of her visions in three sections – six visions in the first, seven in the second, thirteen in the third – forth with her estimation and commentary on the nature of the Divine and the part of the Church as an intermediary betwixt God and humanity. She depicts God as a cosmic egg, both male person and female person, pulsing with love; the male person attribute of the Divine is transcendent while the female is immanent. It is this immanence which invites rapport with the Divine.

Hildegard believed that, prior to the Autumn of Human, God was worshipped by celestial song which, later on the Fall, was approximated by music as humans now heard and understood it. Music, then, was the best expression of one's dear for, devotion to, and worship of God. In keeping with this belief, she ends the Scivias with the text of her morality play Ordo Virtutum and her Symphony of Heaven, one of her primeval musical compositions.

Throughout her time at Disibodenberg, Hildegard routinely practiced what is known today every bit "holistic healing" using resonant spiritual energies and natural remedies to maintain health and cure illness and injury. Between 1150-1158 CE she composed her Liber Subtilatum ("Book of Subtleties of the Various Qualities of Created Things") comprised of 2 sections, her Physica ("Medicine") and Causae et Curae ("Causes and Cures of Illness"). She argues that human beings are the acme of God'south creation and the natural world exists in harmony with humanity; humans should care for nature and nature will practise the same.

Her concept of health was based on the prevailing understanding, derived from ancient Greek medicine, of a human body's health depending on the residual of four humors of the body: sanguine/peaceful/dry (blood), choleric/angry/hot (yellow bile), phlegmatic/blah/moist (phlegm), melancholy/depressed/cold (black bile). Hildegard'southward conception of the humors differed slightly but still conformed to the traditional understanding. When these humors were in balance, the body was in optimum health; sickness indicated imbalance. Hildegard recommended herbal remedies, hot baths, proper slumber patterns, a healthy nutrition, and a positive attitude to keep one in balance or bring a sick person back to a balanced, healthy land.

An essential attribute of wellness was virtuous behave and Hildegard addressed this in her morality play Ordo Virtutum ("Society of the Virtues"), completed in 1151 CE. The play depicts the struggle of the soul, trapped in the flesh, between the call of the virtues and the temptations of the devil. This work was performed past Hildegard and her nuns as the chorus of virtues and the soul (a female person voice), male clergy singing the roles of the patriarchs and prophets, and about likely Volmar in the role of Satan – the only character in the play who does non sing since Satan is incapable of producing music, the true praise of God. Ordo Virtutum is the oldest medieval morality play and the but medieval musical extant.

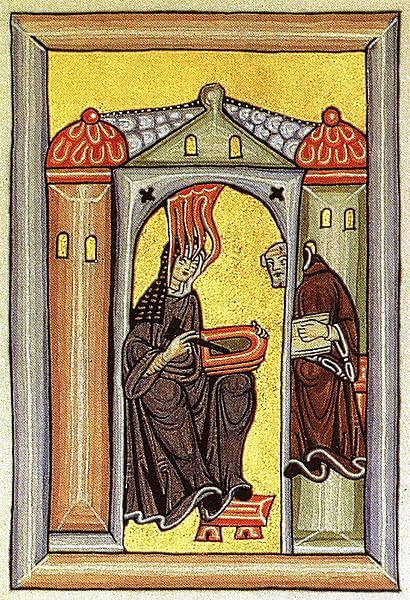

Illustration of Hildegard of Bingen from Scivias

Hildegard was particularly proficient at Rupertsberg and adjacent produced her Liber Vitae Meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits") between 1158-1163 CE. This work expands and develops the theme of her earlier play equally information technology discusses the struggle of the soul betwixt virtue and vice, the true nature and concluding rewards of both, the reason for the soul's struggle, and the immanence of God'due south presence and redeeming love. In this work she also wrote on human sexuality, specifically female person sexuality, describing a woman'southward orgasm every bit the spiritual force which enfolds the man'due south seed in the womb and holds it in that location. The depth of the passion the parents felt for each other during sexual activity would make up one's mind the child's character; if they were in beloved, so the orgasm of both would be strong and the kid would be healthy and happy; if they were non, so the kid would exist biting and imbalanced.

She then wrote her grand theological opus, Liber Divinorum Operum ("Volume of Divine Works") between 1164-1174 CE, which drew together the themes of her previous works but elevated all through the grand scale of her further visions and explication of the nature of the Divine Dear (Caritas) and Divine Wisdom (Sapientia) represented as feminine energies radiating light.

Her concept of Viriditas is as well explored more fully in this work. The 'greenness' of the natural world is reflected in the 'greenness' of the human soul receptive to the Divine, which blooms to life once continued to the cosmic life force. Cut off from Divine Love, the soul is at the mercy of vice which leads only to misery and decease. The natural and life-affirming choice is to embrace the Divine as the essential and enduring energy of existence, recognizing that the virtues phone call one toward an elevated, transcendent reality. Music, of course, is intertwined with this concept of 'greenness' as it elevates the soul in praising the source of all life.

Correspondences & Controversies

While composing her written works and musical scores (still pop and performed in the nowadays day), Hildegard besides kept upwardly a correspondence with kings, queens, ecclesiastical authorities, and many others. She exchanged letters, still extant, with such medieval luminaries as Bernard of Clairvaux (l. 1090-1153 CE), Thomas Becket (50. 1118-1170 CE), Henry Ii (l. 1133-1189 CE), Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE), Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany Frederick Barbarossa (l. 1122-1190 CE), and many others. She was never afraid of controversy or criticism and never failed to stand up to patriarchal ecclesiastical or secular say-so for what she believed was right.

Fifty-fifty in her early eighties, Hildegard refused to be bullied or cowed by male person dominance figures.

She went on four speaking tours which included stops in Cologne, Trier, Wurzburg, Frankfurt, and Rothenburg as well as trips into Flanders. These tours were expressly to evangelize sermons to predominantly male audiences in spite of St. Paul's injunction against women speaking in the presence of men, having authority over men, or pedagogy men (I Timothy ii:12-xiv, I Corinthians eleven:3, I Corinthians xiv:34) and a central focus of her sermons was the corruption of the church building and the need for immediate and drastic reform.

Even in her early eighties, Hildegard refused to exist bullied or cowed by male authority figures. The Archbishop of Mainz ordered her to exhume the torso of a young human being, buried in holy ground at Rupertsberg, who had died excommunicated. Hildegard refused, claiming that the homo had sought absolution and received grace and it was only the Archbishop'south personal stubbornness and pride which prevented him from recognizing this. She traveled twice to Mainz to plead her case but was denied, and her convent was placed nether interdict. Just when the Archbishop died was the interdict lifted and Hildegard and her nuns regarded as having been returned to a state of grace in the Church.

Conclusion

Aside from her contributions to theology, philosophy, music, medicine, and the rest, Hildegard invented the constructed script of the Litterae ignotae (alternate alphabet), which she used in her hymns for concise rhyming and, mayhap, to lend to her text a sense of some other dimension and college airplane. She likewise invented the Lingua ignota (unknown language), her own philological construct of 23 letters which served to separate and elevate her gild from the mundane world.

In spite of her accomplishments and fame, the Church continued to regard women not only every bit 2d-grade citizens but unsafe temptations and obstacles to virtue. The highly influential Bernard of Clairvaux claimed that a human being could non associate with a woman without desiring sex with her and the canonical society of the Premonstratensians banned women from their order challenge to have recognized "that the wickedness of women is greater than all the other wickedness in the world" (Gies, 87). It was precisely this kind of misogynistic mindset that Hildegard struggled against not only inside the Church simply in medieval society at large.

Yet, the significance of her work was recognized past the Church and she was singled out equally a woman of note. Four attempts to canonize her were mounted and, although she is oftentimes referred to as Saint Hildegard of Bingen, none succeeded. She was but beatified, non canonized, in 2012 CE, although regarded by many as fitting the criterion of a saint. Her famous visions are today interpreted as symptoms of a migraine sufferer but this has in no mode detracted from her reputation.

In 1979 CE, the artist Judy Chicago included Hildegard of Bingen in her installation artwork The Dinner Party (currently on brandish at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, Usa), an ornate triangular tabular array with settings for 39 women from history and literature jubilant their contributions to world culture and knowledge. The names of another 999 women are engraved on the floor the table rests on. Hildegard would no doubt enjoy her place at the table between Eleanor of Aquitaine and accused-witch Petronilla de Meath (1300-1324 CE), executed for heresy; two of the many women celebrated in the work for who they were and the message they continue to offer the world.

This commodity has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to bookish standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Hildegard_of_Bingen/

0 Response to "Hildegard of Bingen Was Born Into a _____ Noble Family"

Post a Comment